Lafayette’s World War II Poster Collection: The Construction of Empathy

Russian War Relief Map of the United States, illustrated by Elliot Anderson Means, 1943

Over the course of the Spring 2023 semester, as a Student Assistant for the Skillman Library Special Collections, I had the opportunity and privilege to handle the College’s collection of archived World War II posters and maps. Originally created during the war, the collection currently contains over 300 objects, organized into folders correlating with the objects’ purposes and themes, as well as the missions of the various government and private agencies or organizations that produced the objects. I was given responsibility for documenting information; the objects’ titles, dates, dimensions, publishers, and illustrators, and transcribing the data into ArchivesSpace, an open source web-application for managing archival information. While I was unable to catalog the entire collection, it is hoped that future Student Assistants will be able to complete the documentation, so that Lafayette students, faculty, and alumni will have greater access to the materials for their education, research, and general interest.

As I reviewed the collection, I paid attention to how the posters functioned as pieces of propaganda supporting the war effort. The posters served a variety of purposes, such as promoting a sense of patriotism, advertising war bonds, stressing the importance of conservation and rationing, collective effort, and military recruiting. There was one recurring function particularly interesting to me due to the manner in which it subverts common conceptions of how propaganda operated during this time period, and its modern relevance: eliciting empathy for foreign nations and peoples suffering due to the conflict. As there was no fighting within the United States proper, the majority of Americans did not have direct insight into the scope of the violence, death and destruction that the Axis powers wrought on occupied and contested countries and populations. Pieces of propaganda were therefore created to transform the violence occurring overseas from an abstract concept to a truer reflection of the horrors of the war, thereby encouraging people to support relief organizations and efforts.

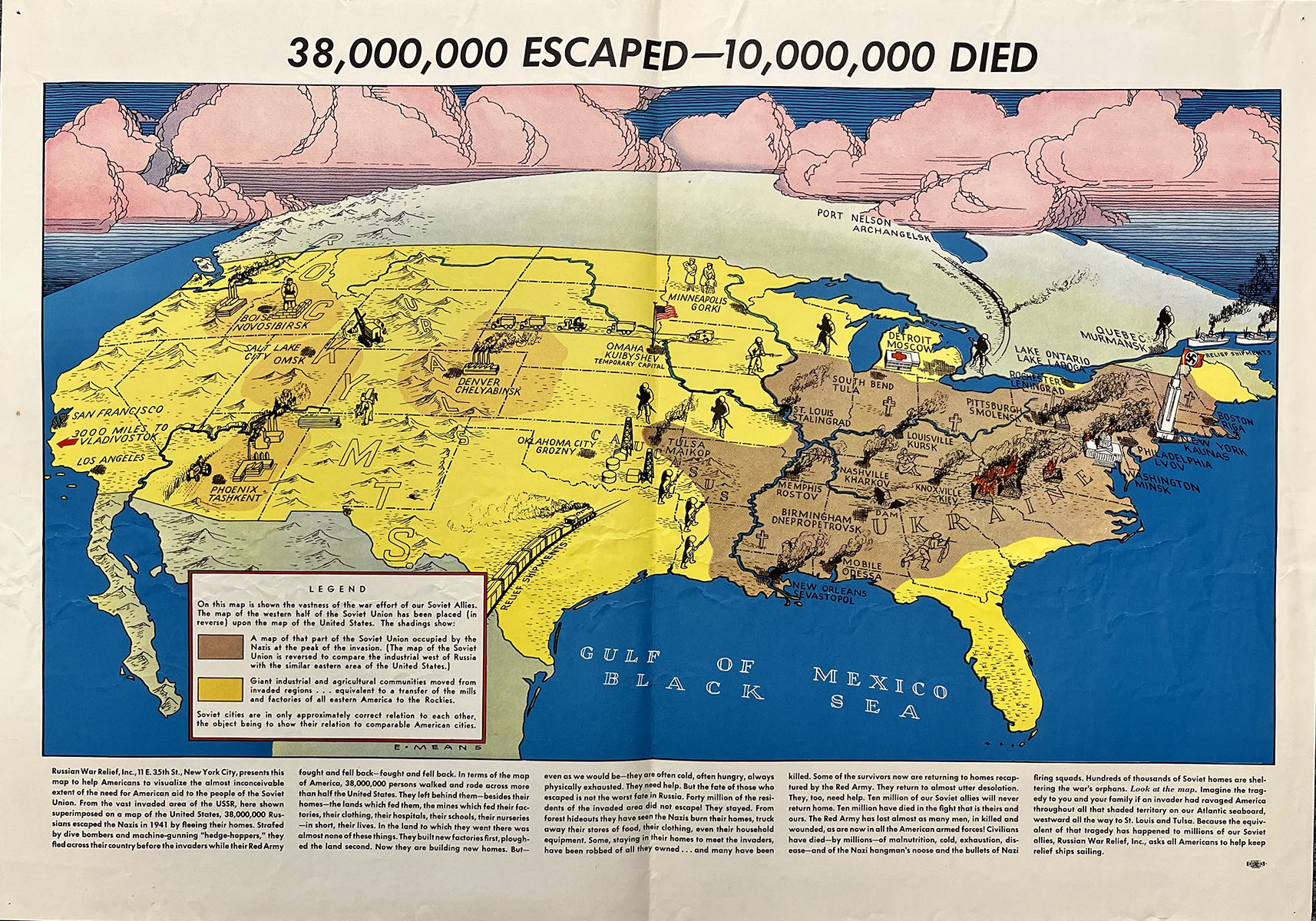

One object in the archive that I found to be particularly interesting in how it attempts to produce empathy is a 1943 piece entitled “38,000,000 Escaped – 10,000,000 Died,” Published by Russian War Relief Inc., an American institution created to aid Russian civilians displaced by the war, and illustrated by artist Elliot Anderson Means. The piece is a map of the United States. However, as the legend of the map explains, the western half of the Soviet Union has been superimposed on top of the map, with Soviet cities paired with American cities and regions of approximately the same size; Ukraine covers the East Coast, Moscow is near Detroit, and the West comprises The Caucuses. The gray colored portion of the map represents areas of the USSR occupied by the Germany at the peak of the invasion, and is accompanied by provocative images of Nazi aggression transposed onto the American landscape and landmarks: A swastika flag flies on the Empire State Building in New York City (Kaunas), in Washington D.C. (Minsk) the Capitol building is on fire, and Christian grave markers are placed across the landscape from the east coast to the Mississippi River. Smoke rises from numerous cities, and near Nashville (Karkov) a woman with a headscarf crouches and aims a rifle, representing those within occupied territories who continued to fight back against the German invaders.

The artist transforms a map of the American home front, which had seen no actual battles, into a war torn battleground, in doing so creating a propaganda piece directed at American civilians who, while hopefully supporting the war effort, still likely had difficulty comprehending the scope of the damage wrought by the Nazis. By superimposing the Soviet Union over the United States, the events of the war become more than abstract statistics. The use of imagery of a German-occupied East Coast, with the Nazi flag waving above one of the country’s most recognizable landmarks, evokes a sense of fear at the possibility of an Axis invasion of North America and what it could entail, and draws a line of connection between this hypothetical fear and the reality that people in the occupied Soviet were territories living on a day-to-day basis. Through this evocative imagery, the poster sends a message to viewers that those fighting and dying on the other side of the world are not as far removed from Americans as many would think, due to cultural and societal differences, and that they are deserving of empathy and the resources needed to aid in their fight against fascist oppression.

While the map is directly linked to a specific moment in history in which international cooperation was required to combat a large-scale threat, it is apparent to me how the content and form are still fiercely relevant, especially in today’s political and social climate. The depiction of the American East Coast as a war ravaged Ukraine holds new meaning, given totalitarian Russia’s recent invasion of the country. The descriptions of the displacement that millions of Soviet citizens went through in the 1940s also reminds me of current refugee and immigration crises all over the world, as people seek asylum while often facing xenophobia from those unwilling or reluctant to help.

What I find most affecting, in a specifically American context, is the imagery of the Capitol building in smoke; a worst case scenario at the time of the map’s creation, which seems much more pertinent after the 2021 Capitol riot, in which the severe threat to the democracy came not from foreign invaders, but politicians as enablers from the political right who stirred up fear, hate, and paranoia in order to preserve their own power.

But despite the harsh reminders of the current reality the poster evokes, it also provides a sort of roadmap of the ways to fight back: resilience and empathy. The image of a Soviet woman with a rifle, originally representing Soviet citizens’ ongoing fight against the invading Germans, can now, in a modern context, represent marginalized communities and their current efforts to combat the Right’s jingoism and prejudice. Simultaneously, the overall purpose and form of the object, which sought to invoke a sense of compassion for people in a distant land, can now serve as a reminder of the importance of having empathy for marginalized or scapegoated groups within this country’s borders. While it may be easy to turn a blind eye to threats and hardships faced by “others” because it does not directly affect one’s own life, the poster literally illustrates how threats against one group are actually threats against all, and everyone deserves to live without persecution or oppression. The object depicts the harsh and brutal reality of authoritarianism, but it is not without hope for a better future, and both in the original and modern context, the way to realize that hope is through active and unified resilience and resistance.

I believe that my analysis of “38,000,000 Escaped – 10,000,000 Died” demonstrates the continued importance of archives and special collections like those found in the Skillman Library; they offer not only physical reminders of the past, but of the ideologies, social structures, and failings of humanity that have both remained and evolved over time. These objects exist simultaneously in their original context and modern interpretation, and through them we are able to better understand the ways in which current and historic issues overlap and how to respond to them. History does not exist in a vacuum, and as the text at the bottom of the poster reminds us, we need to “look at the map” to see how previous people and actions create ongoing ripples that are still felt today.